Transfer Pricing

Transfer pricing occurs when entities under the same control sell or buy goods and services. The pricing of the goods and services between inter-related entities is referred to as transfer pricing, which informs managers how to determine an optimum trade-off made goal-congruent decisions through a simple system (Anthony and Govindarajan, 2014; Seth 2021, p.1). For instance, an American company with a subsidiary in Africa can sell some products to its subsidiary in Africa, resulting in a transfer pricing. However, the selling entity must consider the market prices to ensure that it sells the products at an arm’s length pricing. Mainly, companies often employ transfer pricing to reduce taxes within their business.

Many businesses are employing transfer pricing in the current business world, and Cummins is one of the companies I know about. An American Multinational Corporation manufactures, designs, and sells power generation products, engines, and filtration. It also offers car-related services such as engine repair, controls, fuel systems, and emission control. Being a multinational company, it has several subsidiaries, including in a number of African countries. As a result, it employs transfer pricing within its boundaries where the parent company sells products to subsidiaries in different countries. An important thing to note is that the company operates in a non-ideal situation, where managers have to figure out the impact of incompetent people, undesirable atmosphere, market prices, freedoms to source, availability of information, and cultural impacts on negotiation.

The Transfer Pricing Context

The company has heavily invested in Africa and has a subsidiary in almost every African country. Africa is still developing, and hence, the subsidiaries are unable to design and manufacture the products from scratch. On the other hand, America is more developed in terms of technology and innovation. Thus, the company designs and manufactures the products from scratch and then sells them to the subsidiaries, especially in African countries. Instead of the subsidiaries buying from third parties, it buys the products such as engines from the parent company, practicing transfer pricing.

Method

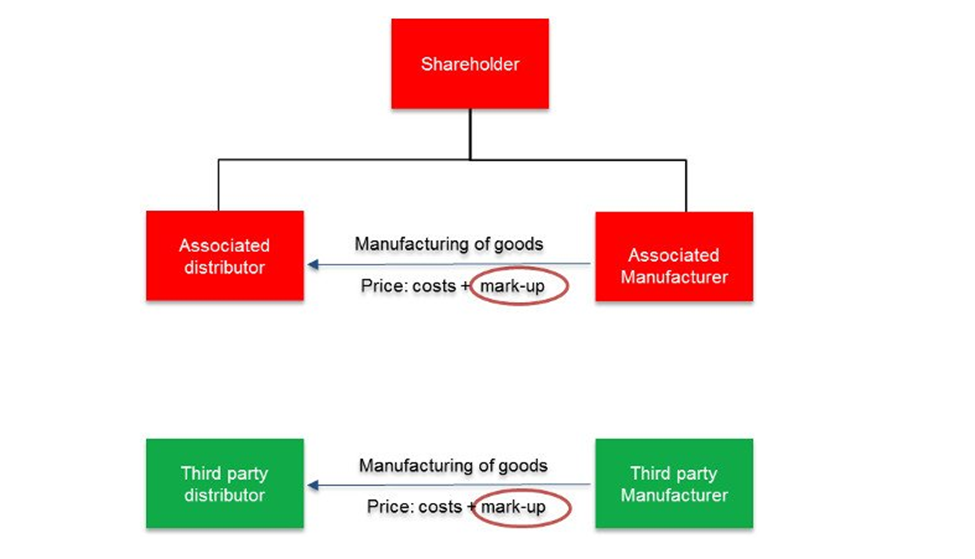

Different methods are used in transfer pricing, and Cummins mainly uses the cost-based method (Anthony and Govindarajan, 2014). It is a method where a related organization compares the terms and conditions made between related and unrelated companies. The method compares a company’s profit if it sells a product to unrelated companies with its profit if it sells the same product to a related organization (Valentiam Group 2021, p.2). The key is determining the markup for both related and non-related companies, which is used to determine the arm’s length price, as shown in figure 1. The method often requires that the profit margins between the two scenarios balance or be close to each other. For example, if selling to a third party would have a cost-plus markup of 55%, then the same cost-plus markup or something close to 55% should be realized if the product is sold to a subsidiary.

Cummins mainly uses this method as a management control system to determine if the transfer price is arm’s length. For instance, it measures the profit by evaluating the cost-plus markup it gets from selling engines to non-related companies against the profit it gets when it sells the same engines to its subsidiary in Africa. Usually, it evaluates the past sales it has had. If it determines that the profit it gets from third parties is higher than it could get from selling to its own subsidiary, it refrains from selling. The vice versa is true where they sell to its subsidiaries if the markup margin is close or fits third-party selling. Notably, these are identified through a predictive model, a robust communication network, and other control systems which suit the situation.

Figure 1: Cost-plus method (source: transfer pricing Asia, 2017)

However, some factors are considered while measuring the arm’s length pricing. One of them is the volume of the products involved in the transaction. The company considers the number of products before comparing the third parties’ sales and those of related parties. Sometimes a subsidiary may order products in bulk, which results in discounts. In that case, the sale might be comparable. The second factor is geography, where the company considers the location of the subsidiary and the third-party company. A third-party company based in Australia might have pricing differences with an African subsidiary. Hence, determining the arm’s length price in the cost-plus method requires the company to consider such factors.

Why it works for the company

The method works for the company because it guarantees against loss-making. In the event that the company would not calculate the markup, it would make huge losses. Comparing profits between businesses between related and non-related organizations helps the company realize which side has more profit than the other and is likely to make losses. For example, the company could find out that selling its products to a subsidiary in Africa results in a low markup than selling to a third-party company in America. This could be contributed by many factors such as the prevailing economic conditions in Africa, the purchasing trends at that particular time, and expenses such as transportation and taxes. In that case, the method enables the company to avoid losses. Consequently, avoidance of losses enables the company to keep growing.

Intended and Unintended Consequences

The major intended consequence of transfer pricing for the company is to increase its profit margin by reducing taxable income. Typically, many companies employ transfer pricing to subsidiaries in various jurisdictions because taxable income varies depending on location (Anthony and Govindarajan, 2014). For example, taxes charged in America is different from those charged in Africa. The company tries to transfer the prices of its products t subsidiaries that are in countries with low taxable income. This way, it is able to reduce the overall taxable income, increasing the profit margin.

For example, suppose Africa’s taxable income is low than in America, and the company sells engines to an African subsidiary. In that case, the parent company might sell the products lower than the average market price without considering the arm’s length price. The parent company will make less profit because it has sold at a lower price, while the subsidiary will get a higher price if it sells the same product at a higher price in Africa. That means that the overall company will profit because a higher profit is realized where taxable income is lower, meaning the taxes charged will be lower. On the other hand, the parent company’s taxable income will also be lower because it made a low profit. This is an instance where cross-functional management fails due to poor control, especially in decentralized companies (Anthony and Govindarajan, 2014). However, it is plausible for managers to create an atmosphere of unity, where stakeholders feel part of the cross-functional system.

The likely unintended consequence is making a mistake and incurring a huge loss that could have otherwise been avoided. The company could limit its chances of getting a higher profit if it fails to accurately calculate the comparable profit margins. For example, transporting engines to Africa could be much more expensive than selling them to a third-party company. If it fails to calculate with accuracy and makes a mistake where it finds out that the profit margins are close for both companies, it could incur huge losses instead of profits.

Anything Else

Despite transfer pricing enabling companies to reduce taxable income, a debate over its use has ensued. This is after three companies, Starbucks, Apple, and Fiat, were sued for evading taxes through the method. According to Zhao, the companies have been trying to evade tax charges by selling their products to their subsidiaries in jurisdictions where taxable income is low (2014, para.2). As a result, they end up evading too much taxes, which is against the law because it gives them unfair benefits over their competitors. Hence, as much as transfer pricing is beneficial, it should also be regulated to ensure that companies do not create loopholes for tax evasion.

Bibliography

Anthony, R. and Govindarajan, V., 2014. Management control systems. London [u.a.]: McGraw-Hill Education.

- FAST HOMEWORK HELP

- HELP FROM TOP TUTORS

- ZERO PLAGIARISM

- NO AI USED

- SECURE PAYMENT SYSTEM

- PRIVACY GUARANTEED

Seth, S., 2021. Transfer Pricing. [online] Investopedia. Available at: <https://www.investopedia.com/terms/t/transfer-pricing.asp#:~:text=Key%20Takeaways%201%20Transfer%20pricing%20accounting%20occurs%20when,burden%20of%20the%20parent%20company.%20More%20items…%20> [Accessed 17 February 2022].

Transfer Asia, 2017. The Five Transfer Pricing Methods Explained | With Examples. [online] Transfer Pricing Asia. Available at: <https://transferpricingasia.com/2017/03/17/five-transfer-pricing-methods-examples/> [Accessed 17 February 2022].

Valentiam Group, 2021. 4 Transfer Pricing Examples Explained | Valentiam. [online] Valentiam.com. Available at: <https://www.valentiam.com/newsandinsights/transfer-pricing-examples> [Accessed 17 February 2022].

Zhao, G., 2014. Transfer Pricing Lands Apple, Starbucks, and Fiat in Hot Water « Global Financial Integrity. [online] Global Financial Integrity. Available at: <https://gfintegrity.org/transfer-pricing-apple-starbucks-fiat-hot-water/#:~:text=Transfer%20pricing%20is%20simply%20the%20accounting%20practice%20by,there%20are%20lower%20taxes%20or%20better%20tax%20breaks.> [Accessed 17 February 2022].