Study Guide for Tourette’s Disorder

Tourette’s disorder is a disorder concerning the nervous system. It affects the nervous system leading to abnormal coordination of movements and speech. According to CDC, about 0.3 percent of children aged six to seventeen get Tourette’s disorder. While this happens in childhood or adolescence, Tourette’s disorder becomes severe as a person advance in age. This paper is a study guide for Tourette’s disorder, explaining signs and symptoms, diagnoses, prognosis, treatment, and the related issues.

Signs and symptoms according to the DSM-5

According to DSM-5, the criteria for Tourette’s disorder include having one or more vocal tics and multiple motor tics simultaneously, although both tics do not need to be concurrent. According to Andrén et al. (2021), a tic is a rapid and sudden recurrent non-rhythmic vocalization of the motor system, is referred to as a tic and is stereotyped primarily and is the hallmark symptom of Tourette syndrome. The inset usually before adulthood, and they must have persisted for more than one year since the onset of the first tic.

Differential diagnoses

The differential diagnosis for Tourette’s disorder includes motor stereotypies, myoclonus, Substance-induced and paroxysmal dyskinesias, and obsessive-compulsive and related disorders. Motor stereotypes include involuntary repetitive movements, which are usually stopped by a distraction. Paroxysmal dyskinesias entails dystonic movements, which often happen voluntarily. Myoclonus is involuntary and entails non-rhythmic movements just like Tourette’s disorder, but it is different by lack of premonitory urge and suppressibility. Obsessive-compulsive and related disorders are rare but occur due to habituation. A key difference is that movements seem more goal-oriented and complex than tics.

Incidence

According to DSM-5, the onset of tics is between four and six years, and it peaks severity between ten and twelve years. Tourette syndrome is estimated to affect about 1 to 100 children in the US (Jiménez-Jiménez et al., 2020). Symptoms can deteriorate or diminish in adulthood. The DSM-5 highlights that symptoms are similar across age groups. Additionally, people with Tourette syndrome are more at risk of associated problems, including obsessive-compulsive disorder, depression, bipolar disorder, and anxiety. This risk or vulnerability changes as children increase age.

Development and course

In children, Tourette’s syndrome has a course that fluctuates with intensified stress, anxiety, and fatigue which intensify the tics. The development of the tics usually reduces when the individual is asleep or when the person is focused on an activity. According to Mataix‐Cols et al. (2021), cocaine and other stimulants and psychoactive drugs usually worsen the tics. The peak of the tics is 9 to 11 years.

Prognosis

Tourette syndrome has no proven cure so far, although the disease can usually improve when the individual approaches adulthood. Even in advanced adulthood, the tics may still occur, but most individuals who continue their therapy experience fewer incidences. Patients with the disease have their life expectancy as average.

Considerations related to culture, gender, age

Notably, there are no clinical variations of tics based on culture, race, or ethnicity. The disorder is common in all ethnic populations and ethnic groups and is more common in males than females. However, the perception of tics vary from one culture to another, and consequently, healthcare choices are related to the tics. Regarding gender, more males than females are likely to suffer from the tics. Otherwise, the clinical characteristics are similar for both males and females living with Tourette syndrome.

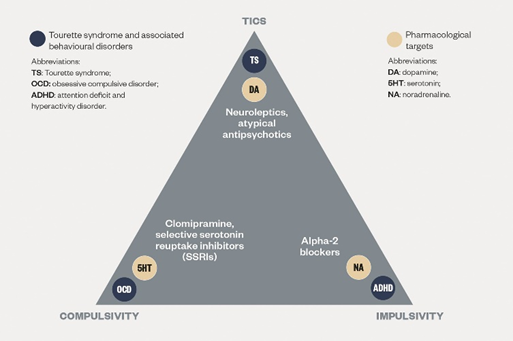

Pharmacological treatments, including any side effects

Pharmacologically, the medications used to treat the disease include blocking and lessening dopamine. The medications include Risperidone (Risperdal), Fluphenazine, haloperidol (Haldol), and Pimozide (Orap) which help in controlling the tics (Muller-Vahl et al., 2021). The possible side effects of the drugs include gaining weight and repetitive, involuntary movements. The most recommended medication is Tetrabenazine (Xenazine), although it may cause severe depression.

Non-pharmacological treatments

The non-pharmacological approaches to relive the tics and related symptoms through self-regulation and assessment practices include biofeedback and behavioral therapies. External stimulation such as acupuncture and brain stimulation are the new ways of non-pharmacological treatment for Tourette.

Diagnostics and labs

The criteria used to diagnose the syndrome include the indication of the motor and the vocal tics, although not simultaneously. The criteria include the presence of motor or vocal tics, age of onset for the symptoms, the duration since the onset, the absence of commonly known causes of such symptoms, and the order of symptoms. Tics have to be sudden and non-rhythmic and must not be voluntary regardless they are simple or complex. The persistence criterion for the syndrome is a minimum of one year since the onset.

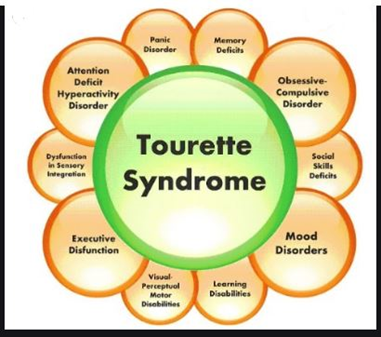

Comorbidities

The common comorbidities in the syndrome include the individual having a deficit in their attention in what is seen as a hyperactivity disorder, OCD, and autism spectrum disorders. Common coexistence issues include depression, substance abuse, anxiety, and child and adult personality.

Legal and ethical considerations

The legal responsibility and mental capacity have been utilized to defend the individual’s neurological disorders charged with a legal misdemeanor, including criminal acts. In this regard, there should be policies and legal considerations that protect people with the disease as they are considered as patients.

Pertinent patient education considerations

The education for this patient includes eliminating the risk of the patient developing depression and engaging in activities such as substance abuse due to discrimination by the public. In this regard, to cope with the syndrome, the patient should remember that tics usually reach their peak in the early teenage era and improve as one gets older.

References

Andrén, P., Jakubovski, E., Murphy, T. L., Woitecki, K., Tarnok, Z., Zimmerman-Brenner, S., … & Verdellen, C. (2021). European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders—Version 2.0. Part II: Psychological interventions. European child & adolescent psychiatry, 1-21.

Jiménez-Jiménez, F. J., Alonso-Navarro, H., García-Martín, E., & Agúndez, J. A. (2020). Sleep disorders in tourette syndrome. Sleep medicine reviews, 53, 101335.

Mataix‐Cols, D., Brander, G., Chang, Z., Larsson, H., D’Onofrio, B. M., Lichtenstein, P., … & Fernández de la Cruz, L. (2021). Serious transport accidents in Tourette syndrome or a chronic tic disorder. Movement disorders.

Müller-Vahl, K. R., Szejko, N., Verdellen, C., Roessner, V., Hoekstra, P. J., Hartmann, A., & Cath, D. C. (2021). European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders: summary statement. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 1-6.