Democracy vs. Authoritarian: The rise and fall of Venezuela

Venezuela’s constitutional downfall is not only a national concern and also an international one. For the past 13 years, the globe has faced a democratic crisis. According to Freedom House, the loss of democracy has harmed all types of nations. As a result, the worldwide position of democracy and constitutional freedoms has deteriorated during the last 13 years, and the reasons for this degradation are many (Freedom House, 2019a). The exciting challenge is determining how to concur with these characterization studies of nations’ sovereign capacities. Because this is a question of definitions of the concept of national designations, the solutions are limitless. As a result, new conceptions of government types have evolved in vibrational modes.

Venezuela’s situation is not like any other conventional autocratic government. The country’s autocratic shift has gotten widely observed because of the various issues it had experienced several years ago. Human liberties groups have heavily attacked Maduro for his lack of understanding of the sociopolitical, financial, and psychological disasters. The United Nations did not issue its first assessment of Venezuela’s human liberties breaches until 2017 (Regeringen, 2018). It is no accident that Freedom House states that Venezuela is no more a democratic nation in the same season. The longer time goes by, the more concepts Maduro develops to obtain greater control and authority by using any democrat inclinations (Mainwaring, 2012). In Venezuela, the interaction between democratization and authoritarianism threatens the social and legislative spheres.

Social and diplomatic liberties are safeguards against the government’s intrusion into social life’s social and political domains (Regeringen, 2018). This safety from the meddling of such activities deteriorates in an authoritarian system. This governmental involvement intensified throughout Chávez’s reign due to an improvement in popular acceptance of this meddling in the open, autonomous, civic sphere (Corrales, 2006). As a result, the link between emerging types of authoritarianism and the preservation of civil liberties is not correlated and warrants more investigation.

Research Rationale

Numerous researchers and think tanks believe that Venezuela has been trapped between the Venezuelan people’s democratic and authoritarian ambitions since 1945. For decades, Venezuela “bounced” between democracy and tyranny (Roberts, 2020). Hugo Chavez lawfully ascended to power through an election in 1999, yet he had staged a coup in 1992 and served a prison sentence for it. The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) report explained a trend of bouncing between democracy and authoritarianism using the definition “petrostate,” as well as its negative impact on political stability in developing countries such as Venezuela (Cheatham & Labrador, 2021).

The research refers to the evolution of an idea that shows its intimate links to the era in which it occurs, particularly if it corresponds to the conclusion of a moment or the shift to something superior or worse. The concept of crisis depicts the uneasiness and desire to change the prevailing situation in a specific culture. Venezuela’s latest political background is one of the persistent difficulties that intensified in 1998 with Hugo Chavez’s ascent to authority as a win over the government founded in 1958 after a decade of army tyranny. Like the other Latin America, Venezuela has gone through revolutions from dictatorial regimes to democracies (Smith, R., 2018). Global emphasis has been drawn to the political situation (Monaldi & Penfold, 2014). Since Chávez, ideological researchers have studied totalitarianism in Venezuela. Chavismo and populism were significant elements that led to the growing state power (Hawkins, 2015). Nevertheless, since President Maduro’s election in 2013, Venezuela’s civic and political environment has worsened, and a more authoritarian environment has emerged.

The term “new” authoritarian refers to a new conceptual paradigm defined by certain variables concerning select transitional nations. The concept of “new” authoritarian posits that the employment of legislation in the executive department, the resistance as the adversary, civil society’s commitment to the state, and the deployment of army and armed services may all explain authoritarianism in transitional governments. It is thus intriguing to study how these elements apply in the instance of Venezuela and possibly justify violations of people’s human and civil rights. This may be studied by glancing at the many indications that each element possesses, unique to Venezuela (Lyles, 2001). The emergence of authoritarianism is inextricably linked to violating human and civil liberties. This link is highlighted in Freedom House’s yearly nation studies on voting freedoms and civil freedoms (Freedom House, 2019b).

The level of these freedoms and privileges in connection to liberty and governance is measured by Freedom House.

- FAST HOMEWORK HELP

- HELP FROM TOP TUTORS

- ZERO PLAGIARISM

- NO AI USED

- SECURE PAYMENT SYSTEM

- PRIVACY GUARANTEED

The Study’s Objective

This research analysis investigates how the notion of “modern” authoritarian might describe abuses of human and civil liberties in Venezuela from 2013 to 2019. Numerous variables are included in the theory to describe abuses of folk’s human and legal rights. The conceptual model of “modern” authoritarianism, which consists of four components, will be used to analyze the study subject (Barczak, 2001). The employment of legislation, the resistance as the adversary, civil current societal commitment to the state, and, finally, the military and police force deployment are all considerations. The elements include signs that are special to the variables and the instance of Venezuela. These will rationalize the Maduro management’s actions, which have infringed on civil and human liberties in Venezuela since 2013. To better comprehend how Venezuela’s “modern” authoritarianism is depicted, I’ve included indications of each aspect connected to articles of the Global Convention Privileges that have been violated.

Research Question

Does the resource-based economy of a developing country like Venezuela lead/contribute to authoritarianism?

Research Methodology

This study used a quantitative approach to analyze the GDP per capita and Democracy Index of resource-based countries using the linear regression analysis to see whether there was an association between the two variables. To bolster the findings, another linear regression test involving developed nations and their economic systems might be conducted. The benefit of such a study technique is that it would demonstrate a clear link between the resource-based growth income and the democracy/authoritarianism continuum and how it does not (Coppedge, 2005). The building elements of these institutions were examined in studies on democratization and authoritarianism; nonetheless, I feel that assessing the deployment of theoretical concepts would be more beneficial than evaluating abstract phrases. Despite this, the globe is becoming more authoritarian.

The concept of the social compact is probably as ancient as comparative politics itself. It is based on the premise that each citizen’s duties are spelled out in an implicit pact with their authority. To comprehend the difficulties of democratic human civilization, Socrates, Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau experimented with this idea. The values and finances of the international society evolved in the twentieth century as industrialization swept away outmoded colonial conceptions and assumed global frontiers. Our worldwide reliance on petroleum has grown, reshaping the international affairs environment. The social contract was modified as a result. Oil-rich countries have built a distinct fiscal and cultural interplay between the state and the citizens (Monaldi & Penfold, 2014). Historically, a taxed citizen would keep their administration responsible and ensure that they receive their tax refund and money value. Increased participation in political matters will come from a commercial connection between the government and its residents. On the other hand, an extractive republic hinders the citizens from an active relationship with their sovereign states because the state’s funding is derived from rents/taxes derived from mineral reserves. As a result, a political atmosphere devoid of beneficial collaboration with the public is created.

In my research papers, I identify situations when the three complementary causal processes that link autocratic government with oil sales are most abundantly clear: a rentier impact, a repressive impact, and a revitalization effect. These are linked by a historical retelling of significant events of the individual governments and their oil businesses (Ottaway, 2013). Throughout Venezuelan history, autocratic control has been pervasive, with oil income as the common factor in coups, dictatorships, unstable currencies, and deteriorating quality of life.

According to the rentier impact theory, administrations use oil wealth to reduce societal pressures that would otherwise require responsibility on behalf of the people. This is known as the “revenue impact,” A significant amount of petroleum money leads to fewer taxpayers for the populace. The “consumption impact usually accompanies this,” The administration has spent a large portion of its money on patronage. In Venezuela, the rentier impact is visible in a variety of ways. Oil prices are volatile, and to the detriment of rentier states, they swing in either direction on the pendulum of global affairs. Bolivia’s financial system has become far too based on oil income. This is usually accompanied by the “consumption impact,” The administration invests a large portion of its money in favoritism. In Venezuela, the rentier impact is visible in a variety of forms. Oil prices are volatile, and to the detriment of rentier nations, they swing in either direction on the fulcrum of international affairs (Levitsky & Loxton, 2013). The Bolivian government’s economy grew far too reliant on oil money. Oil accounted for almost 96 percent of the total price of the nation’s exports. This is usually accompanied by the “consumption impact,” The administration invests a large portion of its money in favoritism.

Oil accounted for almost 96 percent of the total price of the nation’s imports. Venezuela depends on foreign importation for economic items that were formerly regionally supplied. These purchases were paid for using the previously indicated oil profits. The Venezuelan government’s fiscal slew of privatizations pushed the country well beyond its limits. The overwhelming infiltration of paramilitary and Chávez loyalists into PDVSA and other government firms has resulted in enormous inefficiency (Gratius, 2022). During the decades of fuel prices booms, all extra money was paid and wasted to the point that the Chavez government was deeply in debt. The absence of reserve cash set aside for the expected volatility of petroleum costs became apparent when the country entered a long-term downturn and had the nation’s largest hyperinflation in 2013-2014.

Nationalization of Petroleum Industries

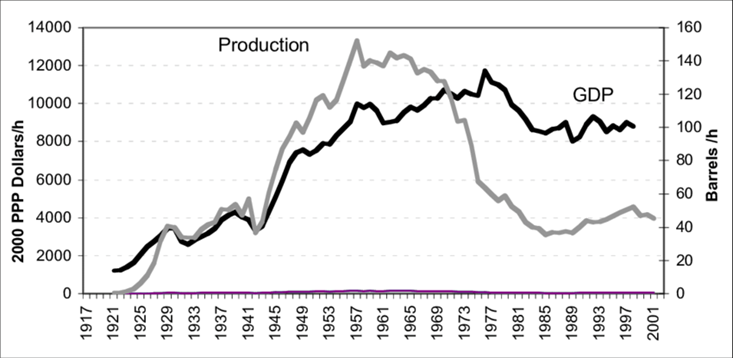

In the mid-twentieth era, Venezuela was a showcase state. They generated roughly 10% of the world’s oil products and had a per capita GDP that was massively greater than neighboring Brazil and Colombia. The government took steps to overcome oil dependence, the infamous affecting economy, and Dutch sickness. In the subsection ‘The New PDVSA & Sowing the Oil,’ I discuss one of these aspirations, Chavez’s “sowing the oil’ plan. The collapse of the envisaged strategy in the second part of the 20th century was inconceivable. The Venezuelan Director of Petroleum products, Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonso, traveled with influential elite groups in Cairo in 1959. He starts to imagine a scheme in which petroleum-producing nations retain control of their oil businesses and are rewarded with a big share of their enormous fortune (Cleary & Öztürk, 2022). His objective was realized a year later, in 1960, with the foundation of OPEC. Venezuela was a charter member and the only country from outside the Middle East to be recognized.

ORDER A CUSTOM ESSAY NOW

HIRE ESSAY TYPERS AND ENJOT EXCELLENT GRADES

Venezuelan petroleum output fell by more than half between 1970 and 1985, when it started to rise gradually. PDVSA’s reputation began to dwindle as it was viewed as an opaque state inside state freedom from government control. The once-popular directors were allowed to determine the direction of PdVSA. They protected themselves from vitriolic public discussions by portraying oil sector strategy as the sole domain of a special group of certified oil professionals (Kestler & Latouche, 2022). Venezuela reopened its doors to international business in 1997. The next year, output had returned to 3.5 million BPD, which was close to its previous peak. Throughout the 1990s, the business was rapidly globalized, and ordinary countrymen and women began to feel left alone. The aristocracy and PDVSA officials had grown infamous for their extravagant habits. The social compact of the previous century – which attended to the masses’ demands if they did not talk much – was no more in use.

Venezuela’s oil production GDP. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Oil-Production-and-Venezuelas-GDP_fig2_237236365

The discontent of the power elite prepared the path for the victory of Hugo Chávez, a guy whose whole legislative strategy was ethical belief and activity against the dominant elite. He said that deregulation of the oil industry was unlawful, which caused friction between bureaucrats and PDVSA officials. Bungled coups and closures gave Chavez control of PDVSA in 2003. He laid off around 18,000 workers and substituted them with his close group of friends and loyalists (Posado, 2022). In 2007, the departure of expertise from PDVSA and the subsequent withdrawal of foreign knowledge rendered it impossible for him to achieve his aim of battling reliance on fossil fuels and dependence on global help.

Crude oil costs in the mid-2000s when Chavez reactivated OPEC and established the ‘new PDVSA.’ His famous commitment was to compensate Venezuela’s impoverished by “seeding the petroleum” straight into the market via humanitarian and communal rehabilitation projects. Chávez would pour huge money into social initiatives whenever petroleum costs were strong. However, he did not participate properly in the capital-intensive oil business. Everything fell apart with the 2007 financial crisis and the seizure of multinational oil firms. There were reportedly occasional deficits in 2007. There was no dairy of any kind on the shop aisles at moments, not fresh, skimmed, or condensed – and this was during a period when oil costs were skyrocketing. It was shocking. According to the rentier impact theory, administrations use oil wealth to reduce societal pressures that would otherwise require responsibility on account of the public (Moynihan, 2022). This is known as the “revenue impact,” A significant amount of oil money leads to less income tax for the populace.

The Suppression Effect

The suppression impact observes that inhabitants of resource-rich nations desire freedom just as much as anybody else. However, economic riches enable more domestic security funding to stifle democratic political ambitions. The Venezuelan constitutional experience of 1958 signaled the start of violent aspirations for authority by both elite and the common populace. Because the impetus for democracy was always economical, the shift from dictatorship was not without a distorted desire for fiscal advantage. Oil-funded dictators in economically impoverished nations can undermine the regulation to keep them in line. Chavez took advantage of soaring crude prices to finance initiatives for crucial constituents like the army and low-income people (Schafer, 2022). Their assistance was critical in removing the autonomous learner from his power. He imposed media controls and removed Supreme Court nominees he considered unaccepting of his efforts. Likewise to what he did at PDVSA. In February 2009, Chavez ‘won’ a nationwide poll, allowing him to continue in government permanently and abolishing direct elections for elected figures.

Chavez’s replacement, Nicolas Maduro, directed the military operation on the dissent. Long after Chavez’s death, his military’s memory might have remained to weaken liberty of expression. Venezuelans have been repeatedly shut down when they have demanded that their leadership be held accountable (Jiménez & Trak, 2022). Militias and illegal conceptions of the law have been used to fight democratic concepts such as voting and nonpartisan discourse. It may be simple to refute this statement by pointing out the rise in persecution during the Maduro government, which has resulted in lesser income. However, this is made feasible by Chavez’s abovementioned measures, which were made practicable under his administration and the deluded Venezuelan government’s adoration.

Conclusion

The relationship between rising forms of authoritarianism and the preservation of civil rights is not connected, and additional research is needed. Numerous experts and think tanks feel that Venezuela has been caught between the democratic and authoritarian aspirations of the Venezuelan people since 1945. For decades, Venezuela “bounced” between democracy and despotism. Venezuela’s recent political history is one of the ongoing challenges heightened in 1998. Hugo Chavez’s ascension to power was a victory against the government established in 1958 following a decade of army oppression. The phrase “new” authoritarian refers to a new conceptual paradigm defined by specific characteristics concerning particular transitional countries.

The GDP per capita and Democracy Index of resource-based nations were analyzed quantitatively using linear regression analysis to discover whether there was a connection between the two variables. Another linear regression test incorporating industrialized nations and their economic systems might be done to support the findings. In my research publications, I highlight instances in which the three complementary causal processes that relate authoritarian governance to oil sales are most evident: a rentier influence, a repressive impact, and a revitalization effect.